CREW research activities include both a decommissioning mapping project and fieldwork on oil decommissioning processes currently underway and expected within Santa Barbara County.

There is no regulatory playbook for decommissioning.

Historically, this hasn’t happened on a large scale or systematically. Oil wells were often just abandoned. Active decommissioning, when it has happened, was seen as happening in isolated, unique cases. But now – if all goes well – we’ll see fossil fuel decommissioning on a global scale.

This project examines questions of how decommissioning should be done. What roles do communities play? When and where does decommissioning take place, and why? Who pays and who benefits financially? How is accountability served? What forms of toxicity must be dealt with? What should be avoided? How can decommissioning build solidarity among impacted communities across borders?

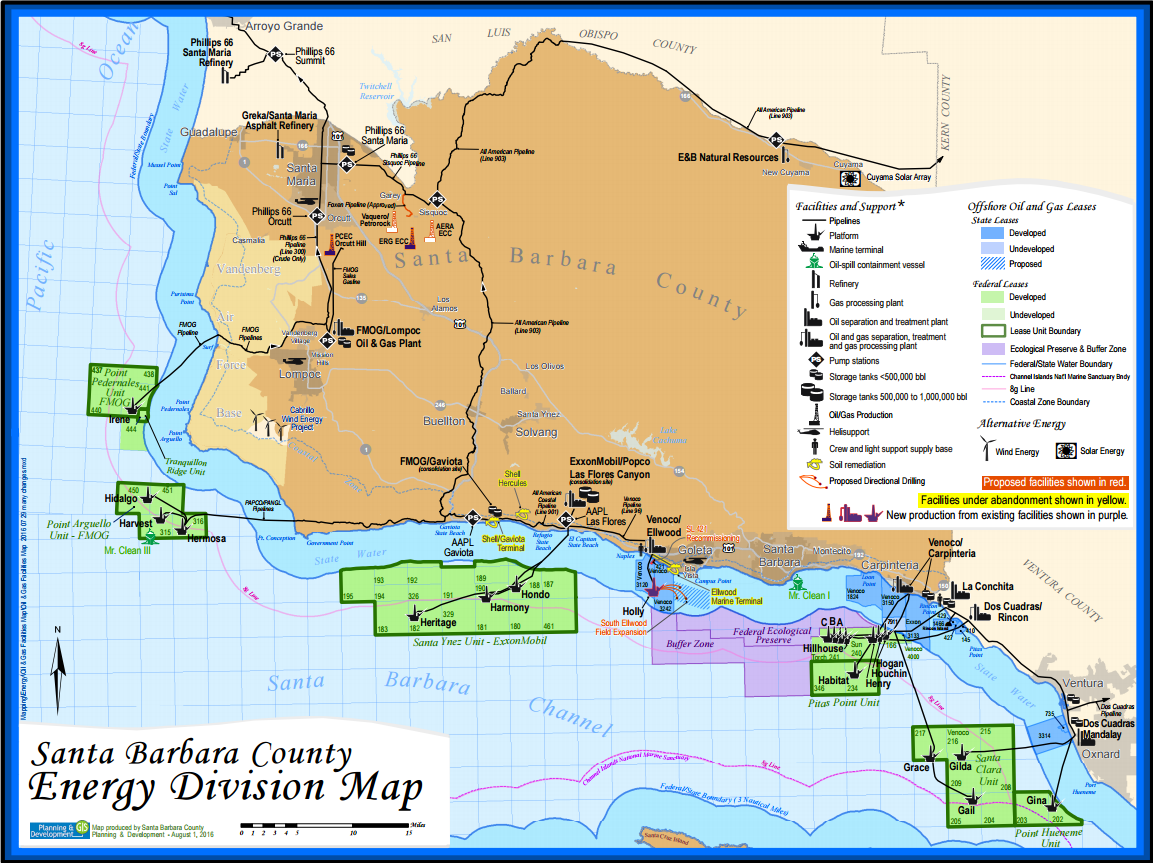

This Santa Barbara County Energy Division map from 2016 illustrates some of the range and scale of oil infrastructure across the county while also, at the same time, highlighting how volatile the oil industry is: in the intervening years, many of these constructions have been abandoned, closed, decomissioned, sold, or have had their ownership transferred away from companies who have gone bankrupt.

This Santa Barbara County Energy Division map from 2016 illustrates some of the range and scale of oil infrastructure across the county while also, at the same time, highlighting how volatile the oil industry is: in the intervening years, many of these constructions have been abandoned, closed, decomissioned, sold, or have had their ownership transferred away from companies who have gone bankrupt.

For more information on the history and politics of oil in Santa Barbara County, consult A Field Guide to Oil in Santa Barbara -- a project by the graduate students in the Mellon Sawyer Seminar on Energy Justice in Global Perspective at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), Fall 2018.

Sites include:

Carpinteria Tar Pits

Summerland

Santa Barbara Harbor

Coal Oil Point

Refugio State Beach.

Clean up costs, sell offs, and accountability

In 2022 Aera Energy, which is a joint venture between Shell and ExxonMobil and accounts for about a quarter of California’s oil and gas production, moved to sell more than 23,000 wells across the state to a German asset management group called IKAV, for an estimated $4 billion (ProPublica 2022). Despite regulatory efforts in California to hold operating companies accountable for the wells they have drilled, operated, and profited from — including surety bonds and special measures to call on former operators to contribute to clean up costs — it is not always clear who is liable nor how those operators will be held to account. Different corporate practices of ‘offloading’ liabilities — together with complex corporate structuring, shell company registrations, and efforts to exploit legal loopholes around bankruptcy — only exacerbate this problem. For example, bonds posted by Aera Energy cover less than half a percent of the $1.1 billion that ProPublica estimates it would cost California to plug these wells based on the average cost to California for past well plugging. Scrutiny of the demise of the coal industry and the costs of coal mine cleanup in West Virginia and other states, coupled with similar practices of corporate restructuring and avoidance, mean that taxpayers are potentially on the hook for hundreds of millions — if not billions — of dollars in reclamation costs.

In Santa Barbara County, also in late 2022, ExxonMobil announced the sale of its Santa Ynez Unit which includes offshore oil platforms (Hondo, Harmony, and Heritage), the Las Flores Canyon onshore processing facility, and the formerly Plains-owned pipeline which ruptured in 2015, causing the Refugio oil spill. The sale also includes 114 wells and 100 percent of shares in the Pacific Offshore Pipeline Company and Pacific Pipeline Company. Production at these facilities has been paused since then. The purchasing company is a newly formed merger of Sable and Flame Acquisition Corp., Sable Offshore Corp., with most of the $643 million purchase price being financed by a $623 million loan from ExxonMobil itself. Sable Offshore Corporation is a consortium of seven companies, of which ExxonMobil is the largest with a 50 percent share. Reuters have reported that ExxonMobil is taking up to a $2 billion loss on the sale.

As tracked by energy scholar Emily Grubert, what has become an all-too-familiar pattern of US coal companies ‘repeatedly going bankrupt, discharging environmental liabilities, selling off assets, and creating massive environmental risk’ is now common in the oil industry. The pattern in the coal industry is not only now familiar, it is also very widespread: “Almost half of all the coal produced in the United States is mined by companies that have recently gone bankrupt” (Macey & Salovaara 2019). This characterizes what Grubert refers to as the ‘mid transition’ of the energy transition — when the inevitable decline of the fossil fuel industries is evident to everyone, including fossil fuel companies themselves and, in response, they find ways to shirk responsibilities by minimize their costs and liabilities. Since even rapid decarbonization will likely take decades, this medium-term future of the “mid-transition” will likely see the ’conventional, fossil-based energy system’ coexist with a ‘new, zero-carbon energy system,’ requiring “explicit and coordinated plans not only for zero carbon phase-in, but for fossil carbon phase-out” (Grubert & Hastings-Simon 2022).

Grubert highlights how Exxon have been deploying these tactics within the oil industry. In addition to the massive sale of wells from Aera Energy to IKAV, mentioned above — and which has been described as putting the latter company “in charge of a living relic of California's early oil and gas production” — in 2022 alone, Exxon has also sold off Barnett Shale gas assets in Texas for $750 million to BKV Corporation; assets in Canada including 567,000 acres in the Montney shale, 72,000 acres in the Duvernay shale, and additional acreage elsewhere in Alberta for a total of $1.47 billion; assets in Arkansas to Flywheel Energy (for undisclosed sum) including 5000 natural gas wells (850 in operation and approximately 4100 not in operation) as well as pipeline and processing properties across 381,000 acres; and a deal to sell $1.28 billion of shares in Exxon Mobil's Nigerian unit that met with regulatory challenges.

CREW fieldwork on oil decommissioning in Santa Barbara County will generate materials to assist community participation in decommissioning, developing a research framework that can be scaled up in the future to assist in decommissioning processes happening elsewhere in California.

Five offshore platforms in the Santa Barbara channel are being decommissioned: platform Holly and Rincon Island, by the California State Lands Commission, and platforms Hidalgo, Harvest and Hermosa by Freeport-McMoRan.

Fieldwork involves engaging with the public hearing processes organized to inform the community about decommissioning to assess how these are run, their perceived effectiveness, and areas for improvement.

In interviews with oil decommissioning workers we ask about the skills, challenges, and goals at the worksite, and systematize information on the policy steps and technical challenges affecting decommissioning.

Vessel VB 10000 engaged in offshore decommissioning work in the Gulf of Mexico (Photo source: www.vbar.com)

Vessel VB 10000 engaged in offshore decommissioning work in the Gulf of Mexico (Photo source: www.vbar.com)

Newsubstance design studio created the piece “See Monster” in southern England in 2022, re-using an old North Sea gas rig (Photo source: dezeen.com)

Newsubstance design studio created the piece “See Monster” in southern England in 2022, re-using an old North Sea gas rig (Photo source: dezeen.com)